While it’s not my intention to be controversial or overly political in this series of posts, I feel I need to explain why my approach to diet can differ to what most doctors and dieticians currently recommend. Most health care providers in Australia will give dietary advice that is in line with a document known as the Australian Dietary Guidelines (ADG’s). Here I will explain the concerns I have about some of the advice in the ADGs for the majority of patients who are trying to improve their health through diet. In this first part of the series, I will explore the history of the ADG’s, how they’ve failed to stem the rise of chronic diseases such as heart disease and Type 2 Diabetes, and how the experts got the advice on dietary fat so wrong. Further articles in this series will explore why our top nutrition authorities insist that we need ‘whole grains’ in the diet; and the approach I think that should be taken at a population and individual level to improve our health. Happy reading!

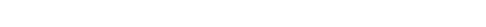

It’s only relatively recently in history that the government has given us advice on what to eat. Prior to the 1950’s and 60’s advice and knowledge about food would be passed down through generations, dependant on geographic location and cultural characteristics. The first version of national nutrition guidelines appeared in Australia in the 1970’s in the form of a pamphlet published by what is now known as the Dietitians Association of Australia (DAA). Jennifer Elliott, a dietitian who was de-registered from the DAA (who also act as the governing body of dietitians in Australia) for seemingly recommending a low carbohydrate diet to people with Type 2 Diabetes, tells the story of the origins of our ADGs here. And this article, written by Professor Stewart Truswell gives us an idea of the nutrition ‘climate’ at the time. Dr Truswell was an academic nutritionist who steered the development of our own Guidelines. Just prior to this time, events in public health nutrition in the US were shaping the formation of the ADGs. American Guidelines are still referenced heavily in the ADG’s to this day. The US Guidelines stem from the McGovern Committee, which was formed in the US Senate in 1968 and ran until 1977 (1). The initial goal of this committee was to develop nutrition policy to address the concerns of malnutrition, particularly in children. Later on, the Committee extended it’s scope to address the issue of over nutrition, in an effort to curb the rising rates of diseases such as obesity, heart disease and diabetes. The policy recommendations of the McGovern committee became the foundation on which the Dietary Guidelines for Americans was based a decade later, then subsequently influenced our own ADG’s. Even at that time, concerns were raised about rushing in national nutrition policy for the US population based on less than robust science. In 1977 Dr Robert Olsen of St Louis University pleaded “for more research on the problem before we make announcements to the American public” to which McGovern (Chair of the McGovern committee) replied “Senators don’t have the luxury that the research scientist does of waiting until every last shred of evidence is in”. So US Dietary Goals and Australian Dietary Guidelines were introduced to the public based on ‘consensus’ of academics at the time, and a main message of that advice was to reduce intake of dietary fat to no more than 30% of total calories in the diet. The natural consequence of such a reduction in fat was the proportion of energy provided by carbohydrate would increase (as there are only 3 macronutrients – carbohydrate, fat and protein – and intake from protein tends to remain fairly constant). The thought at the time was while this advice didn’t have the most robust science to support it, it would be unlikely to cause harm. But is that how things have panned out?

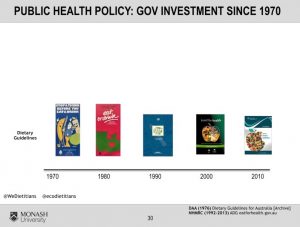

It’s quite obvious that in western countries like Australia and the US, public health nutrition guidelines have not had their desired effect, which is to reduce the burden of chronic disease. This can be seen in the explosive rise in conditions such as Type 2 Diabetes and Obesity since the Guidelines were introduced. These graphics, kindly provided by Dietitian and Health Economist Melanie Voevodin, illustrate the overlay of the rise in obesity in Australia and health spending with the introduction of dietary guidelines and other government ‘healthy weight’ programs.

Many (including myself) would argue that the introduction of Dietary Guidelines has been one of the worst public health disasters of our time. You might say, really?? Do the Guidelines matter that much? Who actually reads them, anyway? And the answer is most people probably don’t read them in their entirety. We certainly didn’t as doctors during our medical training. However, the reach of Guidelines is truly far and wide – having influence from what is taught in schools and offered at tuck shops; to the food provided at every public event, and residential facility; to overarching societal ’norms’ relating to food and nutrition. How could it be that this advice, which was introduced with the best of intentions, turned out to be such a failure? Not only was there a lack of “every last shred of evidence”, the evidence that was available was primarily epidemiological studies which showed weak results. This type of study has now shown to be worse than a coin toss in the likelihood of producing the correct conclusion. Epidemiology is a form of research that looks at characteristics of a population and tries to tie that in with a given health outcome. One major epidemiological study quoted as evidence to reduce dietary fat was the ’Seven Countries Study’ conducted by Ancel Keys. This study noted a ’tendency’ of dietary saturated fat intake to be linked to blood cholesterol levels which in turn ’tended’ to be linked to the development of heart disease. However, Keys himself warned against implying that associations are causation. (Very strong epidemiological associations can imply causation if they they meet certain statistical criteria known as the Bradford Hill criteria. The nutrition epidemiological studies used to form nutrition policy did not meet several of the Bradford Hill criteria.) The other concern regarding the Keys study was that the countries included were selected after a prior preliminary study. Other countries which seemed to disprove the diet-heart hypothesis in that initial research were, for whatever reason excluded from The Seven Countries Study.

John Ioannidis, a Professor at the prestigious Stanford University wrote an opinion piece published in the Journal of the American Medical Association which explains some of the shortfalls of nutrition research (2). He pointed out, “the emerging picture of nutritional epidemiology is difficult to reconcile with with good scientific principles. The field needs radical reform”. What has become apparent is that public health nutrition policy, whose purpose is to reduce the population burden of chronic disease has at best been a failure, and at worst has caused harm to unprecedented millions of people, because the majority of messages given to the public have been based on weak epidemiological associations.

What other types of research could we look at to inform dietary choices? Another type of scientific study known as a randomised controlled trial (RCT) is better able to demonstrate causality between one variable (such as intake of saturated fat) leading to a certain health outcome (such as all-cause or cardiovascular disease mortality). However, RCT evidence at the time of the introduction of Nutrition Guidelines also didn’t support the advice on limiting dietary fat as discussed in this Systematic Review published in the BMJ (3). Even though RCT’s are considered ‘gold standard’, we still can’t exclusively rely on them either to inform our advice. They don’t replicate the ‘real life’ conditions of a free-living individual. In order to meet the criteria of being ‘randomised’ and ‘controlled’, subjects need to be locked up in metabolic wards and follow a prescribed diet that they were allocated to, not one that they chose for themselves. The cost of these experiments are also prohibitively expensive and so they usually only use relatively a small sample size of subjects. The upshot is there will never be that ‘one perfect study’ to trump them all. We will always need to consider the totality of the evidence, along with our own experience (both as clinicians and patients) to inform the dietary advice we give and adopt for ourselves.

With the inherent limitations of nutrition research in mind, let’s look at the logic of why we are told to reduce fat, in particular saturated fat and if this stands up to scientific scrutiny. We’ll start by looking at our Guidelines. Throughout the Guidelines we are told that dietary fat is energy dense per gram compared to protein and carbohydrate and because many people are overweight or obese, we should restrict our intake of dietary fat to help us maintain energy balance and therefore a healthy weight. Sounds reasonable, except for one minor detail. It doesn’t actually work that way in the human body. What actually happens is when dietary fat is consumed in the context of a diet low in refined carbohydrate, the body becomes better at actually burning body fat. The fat-storage hormone insulin comes down and the body is better able to ’tap in’ to burn it’s own stored fat for energy. Consuming dietary fat also has a strong influence on our body’s satiety mechanisms – that is, when we feel full and decide to stop eating. Conversely, consuming high amounts of carbohydrate in the amounts the Dietary Guidelines suggest, stimulates hunger. Ever experienced the 3pm ‘lull’ or the late night ‘munchies’? The hormonal effects of food on our appetite, mood and energy levels aren’t even mentioned in the wordy 210 pages of the Dietary Guidelines. Instead, possible explanations offered for poor compliance with the Dietary Guidelines are “low levels of understanding of the information” and “conflicting information” promoted by junk food advertisers.

If we take a deeper look into the effects of dietary fat on human physiology, we can see that the advice to reduce dietary fat often doesn’t result in achieving a healthier body weight because it inadequately addresses elevated insulin levels. However, we also need to look into some of the trial data of the effect low fat diet advice has had on experimental groups. One such example is the very large Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), where almost 49 000 post menopausal women were randomised to receive a low fat diet according to the guidelines. Health outcomes were measured. One of the study’s findings showed that of the women in the trial who had previously suffered a heart attack and received the low fat dietary advice, there was a 26% increase in relative risk of experiencing a further heart attack. The authors explained this away as “a chance observation, or … confound(ing) by concurrent therapy or co-morbid conditions”. The WHI is just one example. Zoe Harcombe, PhD co-authored a meta-analysis of 10 dietary trials that examined the effect of saturated fat on cardiovascular and all-cause mortality (death from any cause). The authors found “no significant difference in all-cause mortality or CHD mortality, resulting from the dietary fat interventions”. They did note that “dietary modification may reduce serum cholesterol to a marginally greater extent in intervention groups, compared with controls. However, this reduction in serum cholesterol does not appear to translate into an improved survival from all causes or CHD.” In other words, changing the amount and type of fat (eg: substituting saturated fat found primarily in animal products for unsaturated fat found in vegetable oils) can reduce the blood cholesterol reading, but this did not mean that people actually lived longer. This finding that reducing intake of saturated fat will reduce blood cholesterol levels is repeated throughout the ADGs and articles published by DAA. But if you read the wording very carefully as to whether this ‘improvement’ in cholesterol will actually result in you living longer, you will see the picture becomes very vague. This is because there actually is no proof in the literature, not a shred, that reducing your intake of saturated fat will actually make you live longer. Incredible, isn’t it?

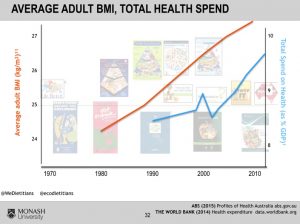

Even though I discussed the limitations of epidemiology as a research method, large epidemiological studies are of some use, and one of these is they can demonstrate a lack of causation. You might have heard of the French Paradox, whereby despite the fact that the French consume large amounts of saturated fat, as a nation, they have a relatively low incidence of cardiovascular disease. Well, it turns out there are many such ‘paradoxes’. Such as the Swiss Paradox, Icelandic Paradox, Swedish Paradox, German Paradox and others. This can be seen in this diagram which shows data from 1998. As the per capita intake of saturated fat across a range of European countries increases, the death rate from cardiovascular diseases decreases (4).

The final point I will raise in my discussion of the flaws of Dietary Guidelines fat recommendations is regarding the sloppy and inaccurate wording used. The Introduction to the Guidelines states: “these Guidelines make recommendations based only on whole foods, such as vegetables and meats, rather than recommendations related to specific food components and individual nutrients”. However, in direct contradiction to this statement, the wording of Guideline 3 is “Limit intake of foods containing saturated fat, added salt, added sugars and alcohol”. Clearly not ‘whole food focussed’ and pointing the finger at “ saturated fat “ as an ‘individual nutrient’ of concern. Guideline 3 then goes on to list examples of saturated fat as “many biscuits, cakes, pastries, pies, processed meats, commercial burgers, pizza, fried foods potato chips, crisps and other savoury snacks”. Clearly these foods aren’t only sources of saturated fat. They are examples of junk foods high in refined carbohydrate. For example, a 280g Whopper Burger contains 12g of saturated fat. Is saturated fat the nutrition culprit here or could it be the 48g of refined carbohydrate? Could the highly processed, inflammatory-promoting vegetable oils also play a role? Here are some other interesting facts about the foods listed in Guideline 3 vs other high fat foods:

* The fat in Potato crisps is comprised of about 1/3 saturated fat. For comparison, the beloved avocado (which by the way, I think is a wonderful food) has about 1/4 of it’s fat content as saturated fat. You never hear about the fact that foods containing so called ‘healthy fat’ can also contain a substantial amount of saturated fat. This calls into question that saturated fat is ‘bad’.

* The companion document to the ADG’s is the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating (AGHE). The AGHE recommends ‘lean meat and poultry’, but allows for up to 40g of ‘unsaturated spreads and oils’ (for adult men) and shows a picture of olive oil. With this in mind, it is interesting to note that 100g of a fatty pork chop, contains less saturated fat than 1 tablespoon of olive oil! Clearly this fact contradicts the oft-repeated advice on fat substitutions. Zoe Harcombe outlines some further surprising examples of types of fats in various foods in this talk.

The fact is that all foods in nature that contain fat contain all 3 types of fat; that is, saturated, mono and polyunsaturated types. It is impossible to “limit intake of foods containing saturated fat” whilst substituting for poly and monounsaturated oils without still consuming saturated fat. Therefore, the wording of Guideline 3 doesn’t make sense, is contradictory and as I’ll explain in a later post in this series should be omitted.

That wraps up Part 1 of my series on Australian nutrition guidelines. The recommendations for the amount and type of dietary fat to consume are not backed up by science, or what actually happens in the body from a physiological and psychological stand point. In the next part of the series I’ll explore the insistence to include the recommended amounts of cereal serves and if this is actually doing us harm or good.

References:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Senate_Select_Committee_on_Nutrition_and_Human_Needs

- Ioannidis, J (2018) “The Challenge of Reforming Nutritional Epidemiologic Research” JAMA 320:10 p969-970

- Harcombe Z, Baker JS, Cooper SM, et al Evidence from randomised controlled trials did not support the introduction of dietary fat guidelines in 1977 and 1983: a systematic review and meta-analysis Open Heart 2015;2:e000196. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2014-000196

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-of- nutrition/article/further-response-from-hoenselaar/F122D4C4F6BEC958EE171146A62EDB9B/core-reader